This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

From the international to the cosmopolitan university

There was a time, back in the 19th century, when the triumph of nationalism, the loss of Latin as a university lingua franca in the West and the creation of national university and scientific systems constrained universities to the political borders of their states. It was not until the last third of the last century that the internationalisation of universities became the order of the day in university strategy, more as an adaptation to political interests in some cases or as an adaptation to the process of globalisation than as a university option. Different scholarships and study options between universities made possible a growing flow of student and researcher exchanges and the beginning of the new trend.

The result of this trend is that today, to a greater or lesser extent, with more or less success, and with some exceptions, the vast majority of the world’s universities have some degree of internationalisation. They have, at least, the rhetoric of internationalisation.

But what do we academics talk about when we talk about internationalisation? What is an internationalised university?

A simple and very generalised definition of internationalisation refers to the presence of nationals from other countries among the different strata of the university community. Thus, a university is very international if among its students, faculty and staff there is a significant percentage of people of different nationalities. Hence we say that a university is internationalised when it has a large number of living agreements with other universities, when it has a large number of mobility and exchanges; when it attracts foreign students and researchers; when its research is published in top-level journals and publishing houses; when its patents are triadic.

But this concept of internationalisation, which is quantifiable and can even be integrated into a synthetic indicator, and which is, moreover, the one that is usually incorporated into both national and international rankings, while important and significant, is to a certain extent superficial. Paradoxically, a university can be very “international”, according to these indicators, and at the same time be very “provincial”.

The fact that students have different passports does not necessarily change the teaching or pedagogy, nor does having different classmates necessarily change the students’ learning experience, if the diversity of origin is not mixed nor integrated. In the same way, mere academic exchange, teacher mobility, does not lead to an improvement in research if this mobility does not generate a different understanding of social contexts or a greater openness to new ideas.

In other words, internationalisation, although a valuable process in itself, is exhausted, it can be superficial, if it does not affect the essence of the university institution, its own activity, if it does not reconfigure its culture and its community, if it does not modify the way in which it teaches and learns, thinks and researches, lives and develops, projects and lives.

Internationalisation is superficial if it does not form cosmopolitan students, open to the world, sympathetic to other cultures, knowledgeable and appreciative of the diversity of social forms. Internationalisation is superficial if it is only an excuse for “academic tourism” or becomes an initiatory rite of “family independence”. Internationalisation is superficial when foreign students are treated in a totally differentiated way and do not integrate, do not participate in academic life.

Internationalisation is superficial if in research we lose the global perspective, when the problem to be dealt with is not seen as a particular case of a problem of Humanity, when we do not consider the solutions that others have contributed, when we do not share…

Internationalisation is superficial, it even loses its meaning if it homogenises diversity under a university culture, when it normalises, when it standardises, when only one, the “other”, the “foreigner” is the one who has to adapt to the forms of teaching, research, life and culture. So a university can have many foreign students, but if it does everything as if it did not have them, if it treats them as tourists, that university is not deeply internationalised.

In short, internationalisation is superficial and meaningless if it does not change us. It is superficial if it only accentuates our own characteristics.

In my opinion, universities must find the meaning of our internationalisation, beyond rankings or trends, beyond the demands of our students’ employers… beyond that. We have to move towards a profound internationalisation that will lead us to become “cosmopolitan” universities. And not because of fashions or competition, but so as not to lose our own character as a university in the century we are living in.

THE COSMOPOLITAN UNIVERSITY

It is already a cliché to say that technology affects us, but it is a true cliché: technology puts within reach of those who have access to it an unlimited number of possibilities of information and knowledge. The problems we face are also global: from climate change to migratory movements, from gender violence to attacks on democracy.

The University cannot live with its back to, or even lag behind, the world in which its students will develop their lives, just as it cannot lose its central role as a motor for the creation of thought to solve the problems of Humanity, just as it cannot cease to be an open place for criticism and dialogue, without losing its own institutional essence. And a university that is only superficially international would lose it. That is why it must evolve, as it is doing, towards a new concept of university, the “cosmopolitan” university. An “inter-national” university is constituted between different nationalities; a “cosmopolitan” university, between “citizens of the world“. A profoundly international university will necessarily be a cosmopolitan university. In the same way, I am convinced that, in the long term, it will be the cosmopolitan universities that will develop successfully. Being a cosmopolitan university will be, in my opinion, almost a matter of survival.

It is also a matter of time before global universities develop, i.e. universities that offer their services in different parts of the world with infinite possibilities for their students and staff. And I am not talking about a virtual university.

The most successful strategy, so far, of creating global universities, with some failures and not a few difficulties, is the one being followed by some North American universities, with the installation of their own campuses in different countries. But another strategy for creating a global university is also possible, based on the establishment of closer links in a network of pre-existing universities. It would be possible through a gradual process of integration, to create global university structures that increasingly share activities and resources, strategies and orientations, shared governance and common ideas, mission and vision.

In contrast to the strategy of expansion, by exporting a closed model to various parts of the world, which does not necessarily make the universities thus created cosmopolitan, the strategy of integration offers greater possibilities, as it forces the universities that integrate to become so. Creating a global university requires a process of convergence, of understanding, of dialogue, of establishing common standards, of shared governance structures, in short, a major effort projected over time, but I am deeply convinced that this is one of the paths that many universities have to follow in our development in an increasingly Darwinian university world.

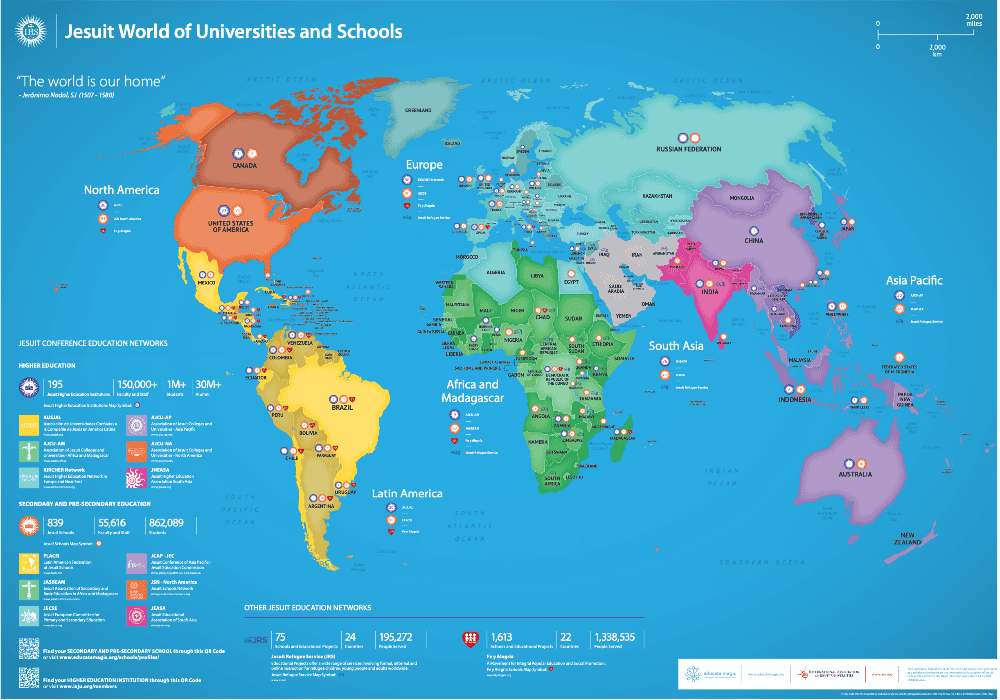

Let me take this opportunity to offer to explore the possibilities of a global university among the Jesuit universities themselves, for not only do we share a mission that transcends the university, but we have common values and ways of proceeding from the same roots, the Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius of Loyola. I am convinced that if a global university by integration is possible, it is within the Society of Jesus. So, as ambassadors of your universities, carry a message of closer collaboration, for we dream of a global university and we want to share that dream.

This text is taken from the inaugural speech of Universidad Loyola, by the Rector of the University, Gabriel Pérez Alcalá