Este sitio web utiliza cookies para que podamos ofrecerle la mejor experiencia de usuario posible. La información sobre cookies se almacena en su navegador y realiza funciones como reconocerle cuando vuelve a nuestro sitio web y ayudar a nuestro equipo a comprender qué secciones del sitio web le resultan más interesantes y útiles.

2015 Paris Climate Conference – COP 21, uneven success

Representatives of 195 nations attended for more than a week the Paris Climate Conference, another one of the important appointments of the international agenda this year. This last weekend at last was reached a landmark accord that will, for the first time, commit nearly every country to lowering planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions to help stave off the most drastic effects of climate change. The deal represents a historic breakthrough on an issue that has foiled decades of international efforts to address climate change.

Traditionally, such pacts have required developed economies like the United States to take action to lower greenhouse gas emissions, but they have exempted developing countries like China and India from such obligations. Scientists and leaders said the talks here represented the world’s last, best hope of striking a deal that would begin to avert the most devastating effects of a warming planet. The new deal will not, on its own, solve global warming. At best, scientists who have analyzed it say, it will cut global greenhouse gas emissions by about half enough as is necessary to stave off an increase in atmospheric temperatures of 2 degrees Celsius or 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit. That is the point at which, scientific studies have concluded, the world will be locked into a future of devastating consequences, including rising sea levels, severe droughts and flooding, widespread food and water shortages and more destructive storms.

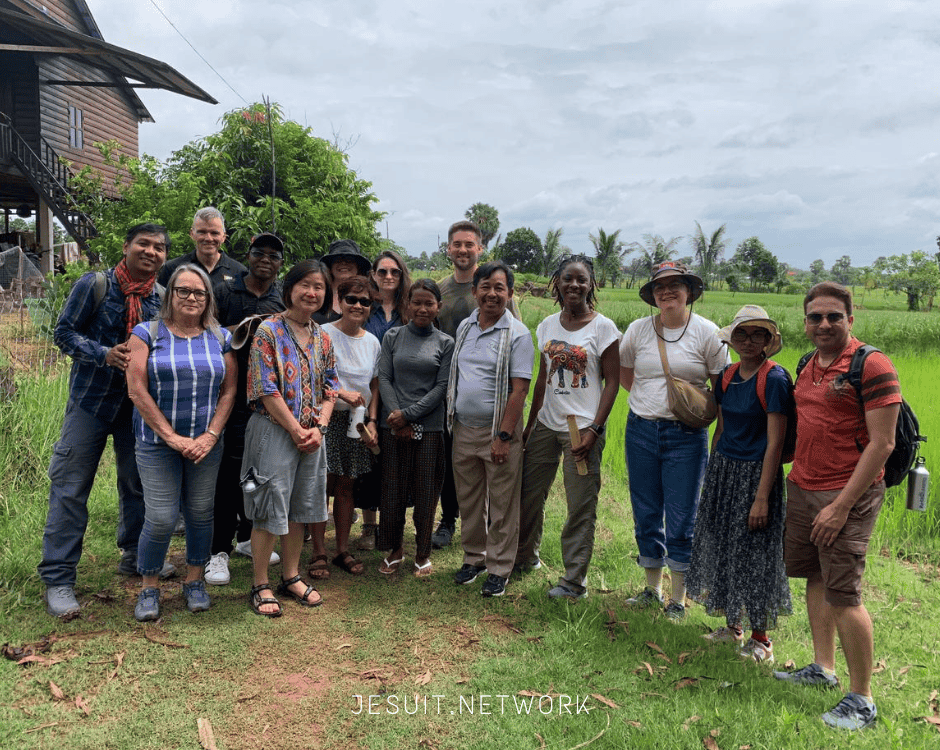

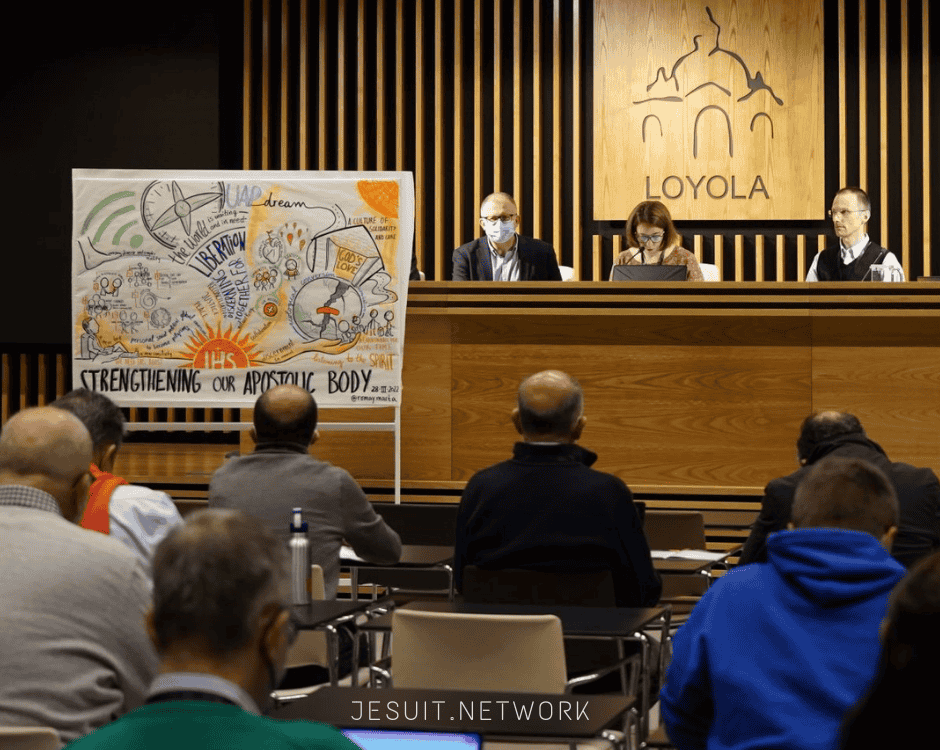

In this matter, the Global Ignatian Advocacy Network Ecology (read their latest editorial here ) as well as the International Jesuit Ecology Project: Healing Earth have followed and focused the Society of Jesus voice along the negotiations and the agenda of the international meeting.

One of the concrete actions took place the last week of November when the Stockholm Environment Institute, Newman Institute, and GIAN-Ecology came ogether and shaped a common ground to understand better the need to integrate sustainability science and values. The Stokholm Dialogue pursued the call to dialogue on sustainability science and values that emerged from previous discussions in Stockholm, Sweden in 2013 and in Bukidnon, Philippines last year. As it can be read in the final document “ Discussions for action on global challenges today need to begin with and integrate an understanding of the reality of a world at risk. Science already shows us the planetary boundaries of our natural and physical world and where we exceed the thresholds, even if there is still much to be better measured.

These boundaries are experienced in the landscapes where we live, in cities or rural communities, in temperate or tropical areas. Local concerns that may not be the most critical globally are obviously connected to the broader pattern of events. It is this growing awareness of global with local and local with global that must motivate local actions relating to the sustainability of people and their landscape. Science alone will not provide solutions for a more sustainable world. Given the magnitude of the concerns as we reach and pass these boundaries, there is a desire to communicate to the world and seek a response that shifts minds and hearts, building solidarity and sustainability.

The effort is to promote greater engagement and understanding among those doing environmental science and those working with local communities for sustained initiatives on resource management, transformative education, and simple lifestyle.”

The COP- 21 final document, however, did not fully satisfy everyone. Representatives of some developing nations expressed consternation. Poorer countries had pushed for a legally binding provision requiring that rich countries appropriate a minimum of at least $100 billion a year to help them mitigate and adapt to the ravages of climate change. In the final deal, that $100 billion figure appears only in a preamble, not in the legally binding portion of the agreement. The core of the Paris deal is a requirement that every nation take part. Ahead of the Paris talks, governments of 186 nations put forth public plans detailing how they would cut carbon emissions through 2025 or 2030.

The individual countries’ plans are voluntary, but the legal requirements that they publicly monitor, verify and report what they are doing, as well as publicly put forth updated plans, are designed to create a “name-and-shame” system of global peer pressure, in hopes that countries will not want to be seen as international laggards.